New York’s recreational marijuana battle sits on the front line of a generational war over American cannabis laws. As debate heats up, USA TODAY Network New York is compiling answers to key questions about legalized cannabis.

As New York plans to encourage black and Latino ownership of recreational marijuana businesses, similar efforts elsewhere are struggling to overcome racially biased pot policing, cannabis industry influence and financial limitations.

From multinational pot conglomerates crushing competition to police disproportionately targeting people of color for marijuana arrests, the first wave of legal cannabis states have faced hurdles to social equity agendas.

Concerns that communities harmed by unjust marijuana arrests could be excluded from the new legal pot industry have prompted a variety of government programs.

(Photo: Getty Images)

Some focused on atoning for prior drug arrests and others sought to improve access to start-up capital, despite industry wide challenges in finding banks willing to deal with marijuana while it still remains illegal under federal law.

What follows is an analysis of New York’s cannabis social equity discussion based on government data and the USA TODAY Network’s ongoing investigation of the issue.

Marijuana money

During a January speech pushing legal pot, Gov. Andrew Cuomo emphasized the financial and social wreckage of decades of marijuana arrests in minority communities, vowing to prioritize them for cannabis business licenses.

“We have to do it in a way that creates an economic opportunity for poor communities and people who paid the price and not for rich corporations who are going to come in to make a buck,” Cuomo said.

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo talks about his upcoming meeting with President Donald Trump during a news conference in the Red Room at the state Capitol Monday, Feb. 11, 2019, in Albany, N.Y. New York pays more in taxes to the federal government than any other state. (AP Photo/Hans Pennink) (Photo: Hans Pennink, AP)

One of the ways Cuomo plans to achieve that is to create a bidding war among current medical marijuana companies in New York interested in expanding into the recreational market.

The 10 companies would submit bids during a state-run auction that determines which ones get licenses to grow, process and sell recreational pot, according to Cuomo’s legislation.

Auction proceeds would fund recreational cannabis business loans for those hit hardest by racially biased marijuana policing, as well as women and disadvantaged farmers. A social equity pot business incubator would get some of the auction money.

Powerful lobbyists and executives for the medical marijuana companies, however, have opposed Cuomo’s pot auction, saying they would instead be open to paying a set amount to aid disadvantaged applicants.

Marijuana arrests

Similar to other states with legal pot already, including California and Massachusetts, Cuomo’s plan includes criteria for promoting minority ownership of marijuana businesses.

Cuomo prioritized applicants who were convicted of an unspecified cannabis-related offense prior to legalization, as well as those who live in communities with disproportionate marijuana arrests.

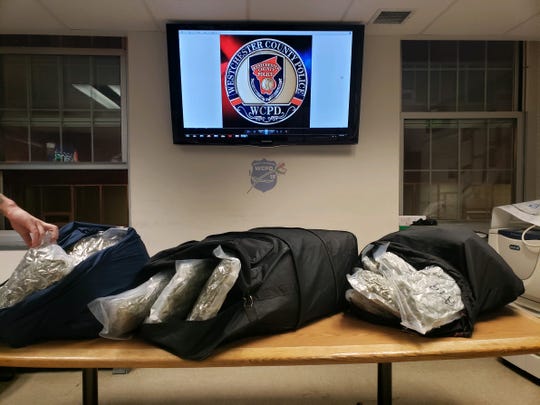

Westchester County police confiscated 54 pounds of weed in two laundry bags after arresting a man during a traffic stop in New Rochelle on April 24, 2019. (Photo: Westchester County Police)

People with an income lower than eighty percent of the median in their county would also get preference in business license decisions, the bill says.

In contrast, New York’s medical marijuana laws prohibits people with drug felonies from running medical cannabis businesses.

Still, Massachusetts recreational pot law went even further than Cuomo, noting it would prioritize applicants who are married to or the child of a person with a drug conviction, according to the state’s Cannabis Control Commission website.

“Criminalization has had long-term negative effects, not only on the individuals arrested and incarcerated, but on their families and communities,” the website states. “We now have the opportunity to redress the historic harm done to those specific individuals and communities.”

But Massachusetts is finding a vast majority of its marijuana licenses are still going to white business owners.

Early findings in Massachusetts show nearly 2,500, or 72%, of the 3,400 active cannabis industry players were white, and just 160, or 5%, were black or African-American. Another 200, or 6%, identified as Hispanic, Latino or Spanish, the cannabis commission reported.

All of the race and ethnicity data was self-reported, and about 430, or 12%, declined to answer the question.

In contrast, the state’s population is 22 percent Latino or African-American. And that same demographic makes up 75 percent of people imprisoned under mandatory minimums for drug crimes, USA TODAY Network reported.

Police bias

And while marijuana legalization has reduced the overall number of marijuana arrests in legal pot states, people of color are still being targeted by police, USA TODAY Network reported.

Even in states with largely white populations, black people using or selling marijuana still face high arrest rates.

In Colorado, which in 2012 became the first state to legalize marijuana, the total number of marijuana arrests decreased by 52 percent between 2012 and 2017, from 12,709 to 6,153, according to state statistics.

But at the same time, the marijuana arrest rate for African-Americans – 233 per 100,000 – was nearly double that of whites in 2017, and that’s in a state that’s 84 percent white.

In Washington, D.C., where marijuana is legal, a black person is 11 times more likely than a white person to be arrested for public consumption of marijuana, according to Metropolitan Police Department statistics.

Similarly, criminal justice data in New York shows racial bias in hundreds of thousands of marijuana arrests between 2000 and 2017.

Health statistics show that whites and African-Americans use marijuana at roughly equivalent rates, which means the disparity in arrests is driven not by use but by police.

Leave a Reply